Competition

by the window

Director:Imaizumi Rikiya

Originally written in Japanese.

A freelance writer Ichikawa Shigemi (Inagaki Goro) was aware that his wife, Sai (Nakamura Yuri), a literary editor has been having an affair, but he is in shock that his anger was not aroused by this fact. Then one day, Ichikawa, whose heart had been drawn to a novel by a high school student writer, Kubo Rua (Tamashiro Tina), whom he met while covering a literary award, confides in her that he would like to meet her if she has a model for her novel. …… This is the second TIFF Competition selection for director Imaizumi Rikiya, who has been presenting three films per year for the past two years. The film, which leaves a lingering impression between scenes and dialogues, warmly depicts the protagonist’s emotional uncertainty of not being able to confide in anyone. The film also warmly conveys the growth of a feeling of acceptance within the protagonist.

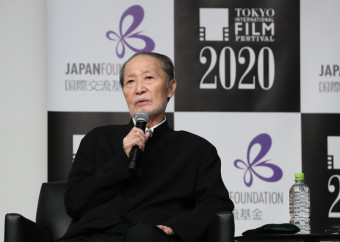

Today we interviewed the director Imaizumi, who has taken a tasteful look at the subtleties of the human heart, which are not always flawless.

This is the second time you have been selected for the TIFF competition after 4 years since “Just Only Love” (18). How do you feel about it now?

Director Imaizumi Rikiya: It is a great pleasure to be selected for the competition again, even as TIFF has been seeking a new direction since its reorganization last year. Last time when Just Only Love was selected, I was told that some jury members questioned the film’s selection, from both artistic and commerciality perspectives. This film also focuses on love, so I am a bit anxious to see how this will be evaluated.

I understand that the project for this film was brought to you with Inagaki Goro as the lead actor. How did you comprehend Inagaki’s personality while writing the script?

Imaizumi: Unfortunately, I was unable to have an opportunity to meet and listen to Inagaki about the script, so I devised the role based on an image I had formed of him from what I had seen on TV and films. About a decade ago, when I just got married, I remembered asking myself, “If one of a couple has an affair and the other one is not angered, does it mean there is no love?” I thought Inagaki would understand this complicated emotion. After he read the script, he said “I know that feeling, too” and we could make it happen.

The press sheet reads, “We have delved deeply into the

Imaizumi: Although many Japanese romantic films do not doubt the feelings of “love”, I have made numerous films that question such feelings and depict trivial matters that have a lesser temperature than those in general romantic films. I like to portray situations that may seem small to the other onlookers, however, the person in question may be quite distressed. I believe that this fear of “not having enough affection when compared to the people” is the best example of such fear. I also think that a film cannot be made on matters that can be resolved by consulting with a few close friends, etc. Rather, I think it is worthwhile to make films in which each person has different answers. And if so, we can debate after watching the film, whether we draw a conclusion or end up asking the question.

While you entrust such more subtle concerns to the freelance writer Ichikawa, acted by Inagaki, it seems that you entrust a bit more public troubles to the athlete Arisaka, played by Wakaba Ryuya.

Imaizumi: When celebrities or politicians have affairs, I feel a strong sense of discomfort with the way they are treated to be erased from the public eye. Although it is a terrible act that hurts his/her relatives, I feel that it is ultimately their own problem. However, once the media gets a scoop, countless anonymous voices gather together to condemn the affair or defend it, claiming that they feel sorry for the unfaithful party. Sometimes, these voices can even cause their divorces. It may seem to be right, but is it? Arisaka’s role includes such questions. Ichikawa is a man that has written only a single novel and called it quits, but perhaps that was a positive decision for him. This character includes the question of whether it is fair to assume that he is unable to write anymore. I wanted to look at how the individuals come to terms with their own situation, even in terms that are prone to prejudice in society.

How did you envision the character of Kubo Rua, the high school writer played by Tamaki Tina?

Imaizumi: Because Ichikawa is a freelance writer, setting Kubo as a writer of the same age would have created a certain kind of rivalry. With that in mind, I decided to portray her younger and depict romance between the younger age group, other than Ichikawa’s, who is in his 40s. Each age group has different feelings of jealousy. I figured that each couple would reach different conclusions naturally.

What do you think about another theme of “letting go” emerging through Kubo’s novel?

Imaizumi: I don’t believe that giving up or letting go of something is not always a negative thing. I consider quitting or letting go of something after experiencing an overwhelming and painful situation to be rather a positive choice, which motivated me to create the second half of the plot.

While there are some directors who wish to regulate all aspects of a film, you seem to be the type who flexibly accepts the opinions of those around you. What do you bear in mind when you are working as a director?

Imaizumi: I have created 17 films so far, but it is still difficult for me to describe my way of directing. The one thing I can say is to create a comfortable situation so that the actors could perform at ease and the staff could effortlessly express their opinions. Since there is a limit to what I can decide on my own, I want to incorporate a variety of ideas and coincidences. I am not particular about the dialogue word for word, so it is okay to change it, but if so, I want it to be more interesting. I don’t wish to shoot the script exactly, rather I care about going beyond the script.

Almost all of your previous films are ensemble cast love stories. What does a romantic film mean to you?

Imaizumi: That’s a hard question. When I first tried to write an original film script, the first thing I was interested in was a love story. One of my close friends once said to me, “Imaizumi’s film is more of a drama film than a romance film,” which made me so delighted.

Your works depict rather passive characters, which may be difficult to understand for Westerners, for whom subjectivity is the basis of human relationships. If you were to leave a comment for them, what would you like to say?

Imaizami: I think that is just one stereotype, just like Italians are considered to be skilled in love. There must be passive people in any country, and I would be happy if they see my work and feel as if it were happening to them. I could be very wrong about this, but I think all cinema buffs are originally on the passive and sensitive side, because I imagine that people who can act independently and lead a good life don’t need movies, novels, or time to relax in the park. I know not many people need my films, but I would like to continue to make films for people who are unable to take action due to negative thinking, just like me.