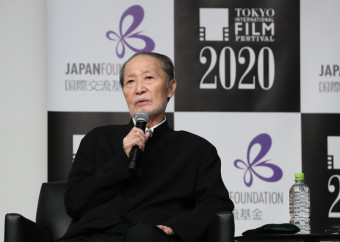

There is a global audience for Japanese film, but it has not grown as exponentially as the audience for Korean film. In a TIFF Talk entitled “The Possibility of Japanese Films Abroad,” two directors with a stake in the increased international success of the industry met on October 30 to discuss opportunities and strategies for the future.

Co-presented by Mitsubishi Estate and TIFF, the conversation featured Kawamura Genki, a megaproducer (Your Name), bestselling author (If Cats Disappeared from the World) and now award-winning director with his debut film, A Hundred Flowers, which is playing in the Nippon Cinema Now section of the 35th Tokyo International Film Festival; and director Ishikawa Kei, whose short and feature films have been embraced by audiences overseas and won awards, with his feature debut, Gukoroku: Traces of Sin, premiering in competition at the Venice International Film Festival and his new film, A Man, premiering in the Venice Film Festival Orizzonti section.

In opening remarks, Kawamura joked that, “We usually talk over drinks, but we never discuss filmmaking. So this is a good opportunity for us to actually talk about films.”

The chat began with recollections of Ishikawa’s recent experiences showing A Man in Venice and Busan, Korea. “The Italian audience was actually calling out Ando Sakura’s name, even though she couldn’t attend the festival”, he said, speaking about the star of the film. “And Tsumabuki Satoshi (another of the film’s stars) had dinner with Tony Leung at Busan International Film Festival. Overseas festivals are always a good opportunity for actors.”

Asked how he felt when he became the first Japanese to win the Best Director award at San Sebastian International Film Festival in Spain, Kawamura said, “I was going there for the first time as a director and there was this sense of ‘Who are you?’ There was this atmosphere of ‘You’re a first-timer, so don’t expect too much.’ Mr. Kore-eda [a San Sebastian regular] scared me with tales of his own first experience at San Sebastian. But then the screening of A Hundred Flowers took place, and the atmosphere changed. The programmers started getting nicer to me. So I thought, Hmmm… maybe something’s going on.”

As for the kind of Japanese films that tend to be invited to festivals, Ishikawa mentioned the differences between commercial and arthouse films: “For arthouse films, I think there’s a [better] chance to go abroad. But getting commercial films screened overseas is a bigger challenge. Big-budget films don’t have a strong need to go overseas.”

And this is clearly one of the reasons that live-action Japanese blockbusters rarely reach international audiences: “If you focus too much on the domestic market, you may not create a universal story,” said Ishikawa. “I lived in Poland for 5 years, and I felt like Japanese films were considered kitsch. I mean, they were never acknowledged as major films.”

Kawamura admitted, “We had my script for A Hundred Flowers translated and sent to Wild Bunch (a European distributor/sales agent) at the beginning of the process, since I felt that if they expressed interest, it could be a viable project. Normally you would begin by getting a Japanese production company behind the film first, so I shouldn’t say too much more about this.”

The men were asked why they felt there was often a disparity between foreign and Japanese films, and began addressing a wide range of formal aspects — from lighting, shooting and editing to acting and directing — and how they often differ from non-Japanese films.

Said Ishikawa, “In Europe, for example, directors of photography have a unique sense of color, and when Polish editors cut films, it’s really different. When I was studying in Poland, they always told us to make things shorter and shorter. There was a scene I wanted to keep, just 1 minute long, and they told me, ‘It may be just 1 min to you, but multiplied by the number of people in the audience, it could be 200 minutes.’ There’s not much pressure here in Japan to cut scenes. It’s considered an invasion of the directors’ space.”

Kawamura concurred. “I think the Japanese industry is gentle on directors,” he said. “The editing process is really the process of making the movie. I cut five scenes in my film, which eliminated two actors’ roles. I had to write letters apologizing to them. But other scenes, I fought to keep.”

He continued, “When it comes to streaming, you wind up trying to add things so that people won’t turn off your film after a few minutes. With A Hundred Flowers, I made it for the theater, because it’s one of the two places without cellphones — the other is in the bath. In the theater, audiences are forced to focus more.”

Kawamura has been behind some of the biggest animated hits in recent years, and when it came up, he said, “Animation is one accepted form of storytelling from Japan. The Weekly Jump writers are doing some edgy stuff that really impresses me. I think they’re on the forefront in terms of communicating to audiences overseas. I think they should be leading the international charge.”

As for live-action films from Japan, Ishikawa noted, “I work with major players on my films, and they’re often prioritizing domestic box office to the exclusion of all else, not thinking about anyone outside of Japan. They would like to be selected by foreign film festivals only so that they can boost domestic box office.”

Inevitably, the topic of Korean films arose. Said Kawamura, “I think only the most brilliant Korean films are being seen overseas. But they’re spending lavishly, and I think their producers and distributors have an ideal business model. In Japan, 90% of the [average film’s] box office is domestic, but I would rather see that figure be more like 50%-50%.”

Ishikawa said, “I think we need to rely more on international distributors. I haven’t yet worked with one from the planning stage, but I would like to.”

Kawamura cautioned that they can be “very blunt about scripts and editing,” which angered him at first, but he learned a lot from the process: “You need to have different perspectives, as well as a cool head.”

Ishikawa noted, “I think the most essential thing is to agree with your producer about your target. It takes 2 – 3 years to make a film, and your producer shouldn’t be too kind or gentle. You need to trust them, you need to share the same values.” You need to have a valuable set of eyes, not only yes-men, so you can get critical views while editing.

“In Venice, when you’re riding the boat to the festival, which takes place on an island, you always overhear what people are saying about the films they’ve seen. And the newspapers carry critiques of all the films. In Japan, we don’t hear the general public discussing the films themselves. We talk about the actors, but the story should matter more.”

Kawamura agreed. “When I worked with Mr. Shinkai and Mr. Hosoda,” he said, “they already knew the films would be shown overseas, so they spent a lot of time thinking about the issues of the time, even issues that were [still on the horizon]. I think Mr. Ishikawa also did the same with A Man. This philosophical question of identity, that we have multiple identities within ourselves, really appealed to people overseas.”

Asked about the chances of Japanese films becoming major in Hollywood, Kawamura responded, “It’s difficult to have a premiere in North America. I think North America is important, although many Japanese are still focusing on European festivals. But after Parasite’s Oscar success, and the success of Squid Game, there’s a greater opportunity for Asian films. Even with subtitles, Americans are enjoying them. Theme is very important, so if we can touch upon [universal themes] and improve the [production values] of Japanese films, I think we really have a chance.”

Kawamura has been working with J.J. Abrams’ Bad Robot Productions as a co-producer on the US live-action remake of Your Name, and he said, “I wrote the screenplay for A Hundred Flowers like a novel. Working with Eric Heisserer [on the US remake] opened my eyes to that. I consulted with him at the planning stages and got some really important feedback. It’s crucial to get different perspectives, if we want to achieve great diversity.”

Ishikawa also suggested that there needs to be a tighter filmmaking community within Japan. “I don’t belong to any Japanese industry groups,” he said, “but fortunately, Mr. Kawamura would come to set and share his candid opinions with me. We should all be more fluid and talk with each other; we should create a community where there’s [no hierarchy], where everyone in the industry is free to come together, mingle and talk. That’s one of the most important roles of film festivals, too.”

TIFF Special Talk SessionsHosted by MITSUBISHI ESTATE Co., Ltd.

Possibility of Japanese Films Abroad

Guest: Ishikawa Kei (Director, “A Man” [Venice Film Festival selection]), Kawamura Genki(Director, “A Hundred Flowers” [San Sebastian International Film Festival selection])