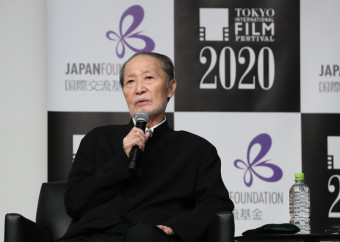

Politics and occult fantasy make for an explosive mix in Tunisian director Youssef Chebbi’s first feature film, Ashkal, which is having its Asian Premiere at the 35th Tokyo International Film Festival. During a Q&A session following a screening on October 29, Chebbi repeatedly addressed the noir aspects of his film, which he acknowledged while qualifying the description as being necessarily limiting.

“Noir and cop movies are the genres I like,” he admitted. “The location of Ashkal is actually a maze. It’s the perfect setting to put two cops together looking for something they are never going to find, so using the noir-cop genre allowed me to distance myself from reality. We always talk about the political situation in Tunisia, but we never dive into it, so I don’t see the point in being realistic. It’s better to invent something through which we can discuss it, and genre films give us that opportunity.”

In Chebbi’s film, two police detectives, Batal (Mohamed Houcine Grayaa) and Fatma (Fatma Oussaifi) are called to investigate the burned body of a man discovered in a half-built condo project started before the 2011 Arab Spring revolution, which began in Tunisia. The cops are confounded by the circumstances of the death, which is deemed self-immolation. But various parties with an interest in the housing development, as well as in the fraught political situation in Tunisia, interpret the death to their own advantage, thus complicating the investigation.

Fatma, for instance, is the daughter of a well-known journalist who heads a commission looking into police brutality following the Arab Spring uprising, and thus her colleagues don’t trust her, making it difficult for her to do her job. Batal has his own problems. He is also looking into several high-level figures in the police department who he believes have been taking money from developers in the hopes of kickstarting the housing project. They try to steer the investigation in a direction that benefits their interests.

What the cops can’t fathom is the motive behind the death, which soon replicates itself in several more self-immolations, and the role of a shadowy, literally faceless man who always seems to be on hand when the victims spontaneously burst into flame.

One viewer suggested that the mysterious crimes were an allegory for “justice in transition,” that Tunisia, having been unsuccessful in jettisoning the repression of the Ben Ali regime, has not rebuilt its society in a satisfactory way. Chebbi thought this analysis valid, but noted, “My purposes for making the film weren’t solely political. I wanted to convey the history of Tunisia using Tunisian motifs—the revolution and self-immolation—but I wanted to approach them from a specific standpoint.

“I used a historical, realistic background to support an imaginary landscape by using genre filmmaking,” he continued. “You’re right that Tunisia has experienced a lot of pain. The violence shown in the movie really exists, and the fire to me represents not only despair but also hope.”

While the scenes of people burning to a crisp are quite powerful, Chebbi said he thinks it’s reductive to consider them a sign of self-destruction. only “We see some people welcoming the fire, and the fire welcoming them,” he pointed out. “I don’t judge. Maybe it’s a gate, or a revelation—it’s certainly not realistic.

“Cinema offers more possibilities than real life. We may not understand something in a movie, but we can feel it. We can feel this man with no face and think of him as an anarchist or a terrorist, or something else. You have that choice as a viewer.”

Moderator and TIFF Programming Director Ichiyama Shozo mentioned that the unfinished housing complex itself was perhaps the most striking element of the movie. “That neighborhood is the main character,” confirmed Chebbi. “It started construction during the Ben Ali regime, which [was toppled] during the uprising. They wanted to build a place where rich Tunisians could live, the powerful members of the regime. Then, after the uprising, construction stopped, leaving this ghost town of high rises.

“My mother inherited a piece of land in this neighborhood, and I came to know it. It was very different from most Tunisian urban areas, which are small and personable. This was like Dubai. It was not designed as a place for human interaction. I would wander around and feel strange, and that’s when I got the idea to make this movie.”

At the end of the Q&A session, Ichiyama asked what directors or films had inspired Chebbi in terms of the film’s noir leanings. His answer was immediate: Kiyoshi Kurosawa. “I watched all of his films during the month before I started shooting,” he said. “I had seen them when they were first released, but my producer suggested I rewatch Cure (1997), since he thought there were similarities with my script that would be helpful—the videos, the mysterious figure. But mostly I found his style and tempo beautiful. I didn’t think of Kurosawa when I was writing the script, but when my producer showed me Cure again it gave me so many ideas.”

Q&A Session: Competition

Ashkal

Guests: Youssef Chebbi (Director/Screenplay)